Short description

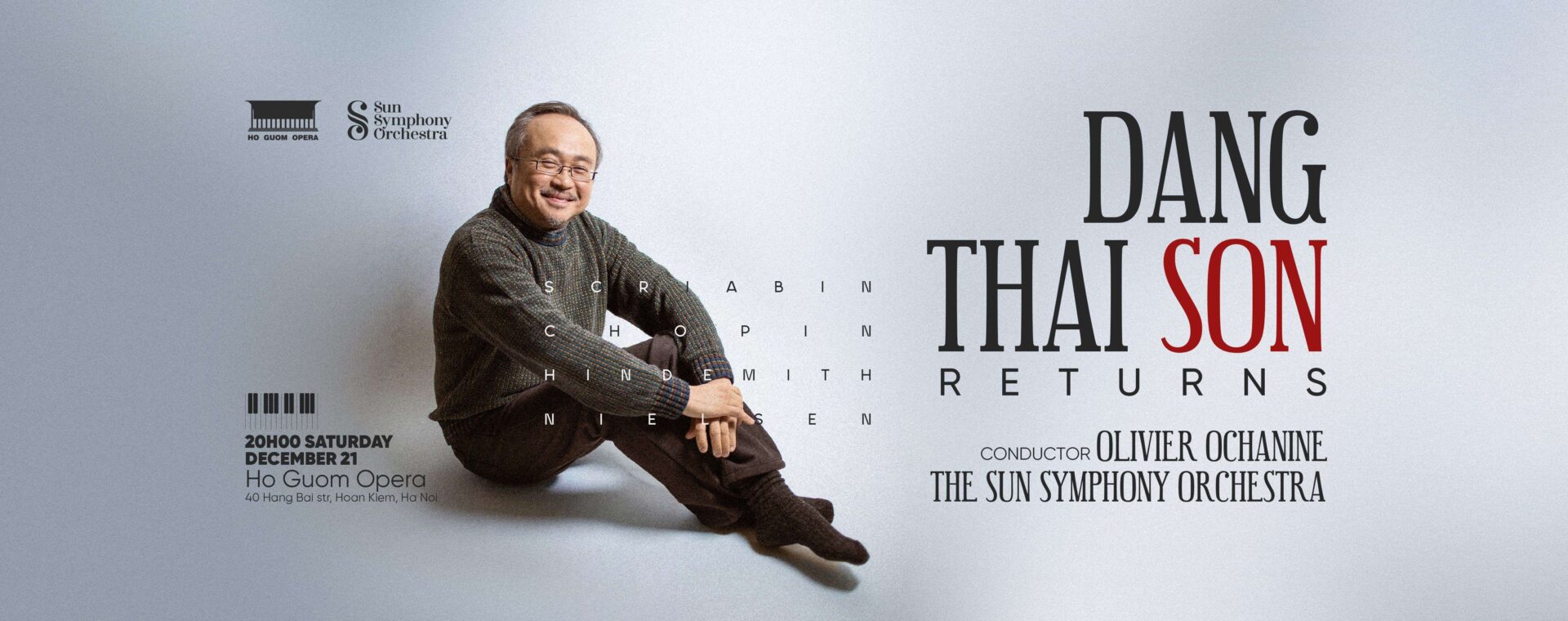

Pianist Dang Thai Son joins Maestro Olivier Ochanine and the Sun Symphony Orchestra for a very special collaboration in December 2024!

SCRIABIN

Rêverie for Orchestra

CHOPIN

Piano Concerto No. 2

Pianist Đặng Thái Sơn

HINDEMITH

Mathis Der Maler

NIELSEN

Aladdin Suite

SCRIABIN | Rêverie for Orchestra

The programme begins with a gorgeous gem from Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, who was also a pianist and composed plenty of music for the piano.

Written in 1898, the short work, originally entitled “Prelude”, features the lush orchestration and the “piquant hamornies” (as Rimsky-Korsakov described them) that Scriabin used in so much of his writing for orchestra. The short work was brought to patron and publisher M.P. Belyaev as a gift; the latter was impressed with the work but chose that it would be better suited with the title of “Rêverie”, or “Daydreams”, as translated from the Russian version of the title.

At the work’s premiere performance, the audience was enamored to such a point that the Rêverie was immediately repeated.

CHOPIN | Piano Concerto No. 2 (Pianist Đặng Thái Sơn)

In his relatively short life (having died at age 39), Frédéric Chopin wrote an enormous amount of music – all of which was for the piano. This output includes various works for piano and orchestra, including his legendary 2 piano concertos. On this program, we feature the also-legendary Vietnamese pianist Đặng Thái Sơn on the Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Minor. This concerto actually was composer first, but published after its counterpart.

Written at age 29, Chopin wrote both concertos mostly for personal use. They are intimate, showcasing Chopin’s personality perfectly. These concertos are different from those of Beethoven or Brahms in that they are almost more solo piano works with orchestral color, an accompaniment serving the pianist, less than an accompaniment in dialogue with the soloist. Biographer Frederick Niecks, who was One of his admirers, nevertheless claimed that “Chopin could not think for orchestra; his thoughts took always the form of the pianoforte language.” However, what Chopin lacked in these areas he made up for with a personality and an originality striking enough to elicit from Robert Schumann the remark: “. . . a genius like Mozart, were he born today, would write concertos like Chopin and not like Mozart.”

We get a sense of a composer writing truly from the depths of his soul. Especially in the slow, middle movements of these concertos, which have some of the most touching melodies and sound textures one can find anywhere. He was a fragile man. Of fragile health and of equally fragile temperament, easily offended, and with an ever-changing mood. This fragility is deeply felt in the concertos.

Scholars have likened the melodies in Chopin’s F Minor Concerto with the lyrical qualities of opera composer Vincenzo Bellini’s arias; both composers admired and respected each other, and both prioritized melody over harmony, using understated accompaniment. This is very apparent in the Chopin concerto, which features an orchestra that really lets the piano have its way and plays largely a supporting role (aside from the introductory passages).

The opening movement begins with a restless theme that is filled with syncopated rhythm. This energetic orchestral opening, of course, recedes into the background once the pianist enters.

It is said that, in the middle movement, Chopin pays homage to his student, Polish soprano Konstancja Gładkowska, with whom he fell in love. The piano “aria” is certainly some of the most inspired piano writing one can find in any music! The middle section of the larghetto is quite interesting in that takes on a recitative-like character, with an operatic piano part accompanied by tremolo in the strings and a thumping heartbeat in the basses.

The finale features waltz and mazurka (a most famous dance from his native Poland). This is a very playful movement that is also quite free, with even a horn call suddenly interrupting the flow before the final dance leads to a thrilling conclusion.

Chopin premiered the concerto in a private concert. The concert was repeated a couple of weeks later, but Chopin, being the easily-offended, frail person that he was, expressed massive disappointment and indignation with the audience’s reaction. It is a sure bet that, were he alive today, Chopin would enjoy his audiences very much.

HINDEMITH | Mathis Der Maler

In 1937, German composer Paul Hindemith, as many other artists, was developing a hate-hate relationship with the Nazi regime. Some years prior, his publisher had asked him to create a musical work based on a fictional account of the real-life, 16th century painter Mathias Grünewald, who lived during the time of the Peasant’s War in Germany. During this war, serfs revolted against their feudal lords before succumbing to hired professional armies. As World War II began to take form, Hindemith elected to approach the subject, putting himself on the Nazis’ radar; the Nazis took notice of his dissidence (“Mathis der Maler” had a clear – if indirect – message of disdain for the regime) and started to ban performances of his music.

In “Mathis der Maler”, Hindemith draws inspiration from Grünewald’s famous polyptych (artwork in multiple pieces) known as the Isenheim Altarpiece. Each of the three movements is based on Grünewald’s bizarre paintings; the opening “Engelkonzert” (Concert of Angels) is a scene of Mary and the baby Jesus being serenaded by angels. The trombones introduce the Hindemith version of the medieval German song “Es Sungen drei Engel” (Three angels were singing). The second movement, “Grablegung” (Entombment) depicts the crucified Jesus being placed in the tomb, and the final movement, based on two of the Isenheim paintings, has St. Anthony attacked by grotesque demons (here one can connect the dots with Hindemith’s St. Anthony representing Grünewald being confronted with his life choices. The other painting represented in this movement shows St. Anthony meeting St. Paul the Hermit. The symphony ends with the sudden introduction of the 13th Century chant “Lauda Sion Salvatorem”, which is followed by majestic alleluias in the brass section.

Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler Symphony is drawn from his opera of the same name, and has become one of his most performed works. In the preface to the conductor score, Hindemith has written “I hope that listeners are initially not over-hostile about the new and unaccustomed elements of this work. Throughout the history of music, we have observed that people have always come to appreciate new tone coloring, melodies, interconnections and formal structures as long as they are underpinned by musical power and logic.” His symphony “Mathis der Maler” certainly is the epitome of fresh tone colors, fascinating harmonies and a novel use of the orchestral instruments (i.e. trombones as angels) as voices in his narrative.

NIELSEN | Aladdin Suite

The Danish composer Carl Nielsen, also a violinist and bugler, wrote 6 unique symphonies, several concertos, a plethora of chamber music works and piano works, as well as incidental music and two operas.

Between 1917 and 1919, Nielsen undertook the composing of music to accompany the Danish playwright Adam Oehlenschläger’s 1805 dramatic play named “Aladdin”. This story, as with the famous 1992 animated Disney film, is loosely connected to the Arabic folktale “One Thousand and One Nights”.

The original performance of the music suffered unfortunate circumstances, including a cramped orchestra that was forced to perform under staircase on the set while the pit was being used for other purposes. When the director of the staged production, Johannes Poulsen, cut out chunks of the music, Nielsen demanded his name be removed from the evening’s performance. The theatre production fared poorly and was withdrawn after just 15 performances.

In Nielsen’s later years, he often conducted selections from the work, and the day before he died following a heart attack, he had the chance to listen to three numbers from Aladdin on a crystal set (early version of the radio).

In 1940, nine years after his death, seven movements were published as the Aladdin Suite and has frequently been performed, to great acclaim.

Of particular significance to this suite is the movement entitled “The Marketplace of Isphahan”, which cleverly divides the orchestra into several smaller orchestras that represent various scenes in the market square. Each section is brought in by the conductor, and is then seemingly left to their own devices (and their own tempo), after which each eventually fades away, giving the listener a peculiar feeling of being immersed in the market scene. It is an ingenious tool used by Nielsen with maximum effect.